(Please hold your cursor over the images to see the caption)

When it comes to talk of motor racing circuits, the inherent dangers of Pukekohe with its fences, narrow space between track and spectators, power poles and trains, doesn’t hold a candle to what they call, the Green Hell — the Nurburgring.

I first drove around this famous track, constructed in the mid twenties, in 1986. I was in Europe for a six-week holiday and hired a 988cc Ford Fiesta — all four speeds of it! Flat out, it would hit 140km/h on the German autobahns and that was where I tended to keep it. I had left two Rover V8s back in New Zealand — a 3500S and an SD1 V8 manual. My experience with the Fiesta taught me I didn’t need a big car and when I returned home I sold both Rovers and bought an Alfasud Sprint! Bad move. I should have bought a Toyota. . .

One surly, grey day I left my base in Holland headed south to try and locate both Spa and the Nurburgring. By the end of the day I had found and driven both.

I found Spa first, quite by accident really. I was driving around in a heavy rain shower getting lost when I recognised the name of a town — Stavelot, which I knew was part of the old track. By now, the new circuit had been completed, but as I found my way onto what was the old circuit I was overwhelmed by a sense of history. From Stavelot village I headed uphill on a badly kept road through a pine forest. I knew I was on the old circuit because there was still Armco on both sides of the road. Suddenly I was on the new circuit — in 1986 this was all still very much “public” roads. Undertyre now was smooth tarmac and the corners had brightly coloured markers and there was new Armco and catch fencing.

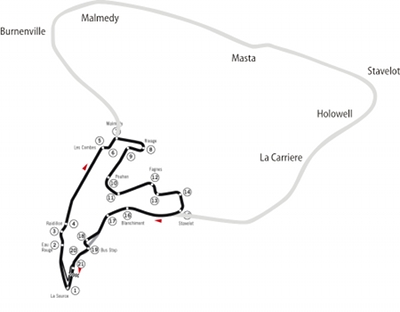

Then I was at La Source, the hairpin and I headed down pit straight — a steep hill with the pit complex on my right and down into the most famous corner in motor racing — Eau Rouge — more a kink at the bottom of a shallow valley. Then it was the steep climb up to where the new piece of track branches off to the right and I continued on to Burnenville, then Malmedy and what was laughingly referred to as the Masta Straight with the chillingly fast Masta kink in the middle. This was a long, long circuit and the downhill “straight” that led into the Masta Kink was two kilometres long, followed by another two-kilometre long run down into Stavelot after the kink.

Here there was still some Armco, but only on what were obviously considered to be the most dangerous parts — the rest was ditches, farm gates, houses and a pub.

Members of the local car club were out in the rain, unbolting the old Armco. Back into Stavelot I was impressed to see that the course ran pretty much across the forecourt of a service station — the pumps were on one side of the road, the workshop on the other! I did a dozen laps, including a couple using the new section which shortens the track considerably.

I was scared by what I saw. This was no place for the faint-hearted — the circuit was frighteningly fast, the circuit narrow and the dangers were horrendous. The circuit opened in 1922 and in 1969 F1 drivers boycotted the race because it was too dangerous. However, sports cars raced there until 1978 when the new link was created, shortening the circuit from 14.1km to 6.9km.

There were many fatalities during the history of the original circuit. The worst year for F1 was 1960 when British driver Chris Bristow and Alan Stacey were killed in the Grand Prix itself, but only after Mike Taylor and Stirling Moss both crashed heavily in practice suffering serious injuries.

Spa was infamous for its weather — some parts of the track could be in sunshine and a dry track, others would be wet — and there was no warning of the change in conditions. I experienced it all that day.

I’ve been back to Spa since, but today there’s a motorway that uses some of the old circuit and the new circuit is now behind locked gates. I got there just in time.

After Spa I set off it search of the Nurburgring with only the vaguest idea of where I was heading. Again, it was a sheer fluke. I was driving around in circles when I suddenly realised I was on a road that actually ran parallel to the circuit. Then low and behold, there was an open spectator gate! So I took advantage and there I was, on the Nurburgring.

I had no idea where I was in relationship to anything, but I had hardly worked my little Fiesta up into a mild sweat when I realised I was in the famous Carousel — that short section of steeply banked concrete where faster drivers line up distant pine trees on the exit. I wasn’t aware of the pine trees but it was late afternoon, the rain had stopped, there were no other cars on the circuit and so I stopped and took several photographs as I completed my first lap.

I did three more laps thinking I might get a feel for the place. But it is so long, so complex and no two parts look the same that I just ended up bewildered and filled with admiration for the drivers who conquered the ‘ring back in the days when it was an active circuit.

My impression after all these years — daunting! It was, by now, in 1986, totally lined with Armco — all 22.8 kilometres of it, but I just could not imagine what it was liked in its heyday.

It was the dangers of both Spa and the Nurburgring that saw Jackie Stewart launch his safety campaign to get, not just these two places, but all motor racing circuits made more safe.

There had been a rough sort of road circuit around the village of Nurburg in the Eiffel Mountain using public roads for many years before it was decided to build a dedicated motor racing circuit. It would be different to the established banked track at Avus in Berlin and would be more like the road circuit around the island of Sicily — the Targa Florio. Construction began in 1925 and took two years.

The circuit was built and was being used several years before A. Hitler came to power, which contradicts a popular story. Hitler only approved the building of autobahns, the creation of the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union Grand Prix cars and the VW people’s car — the KdF, but not the Nurburgring. He was a car enthusiast, sad to say.

The ‘ring was not only used for car and motorcycle racing — but it was also decreed a one-way toll road that the public could drive on. Thus was established a practice that remains today a totally ingrained part of German motoring lore.

Originally the full track was 28.265km long — the Whole Course — but there were internal connection roads so that four circuits could be configured. Using this, they could arrange a shorter circuit of 7.77km — the South Loop, a warm-up circuit around the pits of 2.28km — the Finish Loop and the Northern Loop of 22.8 km. It was this final circuit that eventually became the focus of most of the racing and was the legendary Nordschleife.

After the Stewart instigated safety campaign, a new, modern stadium type of circuit was construct and it is also called the Nurburgring.

The Nordschleife is still used for the public to drive around and also, famously, testing. There are also incredibly popular 24 hour races that draw hundreds of competitors from around the world — including New Zealand! How fast a new sports car can lap the Nordschleife in testing has become a benchmark of how fast that car is.

Since that first visit, I have been back to the Nordschleife half a dozen times. On that first visit I was obviously lucky and stumbled upon a gate that had been left open after the place had closed down for the day. I saw nobody and the various buildings were all closed and shuttered for the day.

There is an excellent museum here with a changing variety of classic racing and sports cars on show. On one visit I saw the only Amon F1 car ever built. It’s since been sold and appeared in New Zealand last years.

The fact that the Nordschleife still exists and is so widely used is a testament to the German attitude towards high speed driving. Not everyone who goes there for a spin on their bike or in their car goes as fast as they can. Many family groups just potter around to say that they have driven the Nordschleife. So the mix of cars on public days can be extraordinarily varied — people movers, GT cars, powerful motorbikes, road cares, supercars, modified cars and even buses.

There are few instructions. You go to a booth and buy tickets for as many laps as you want. The only instruction really is that you can’t do a flying lap — you have to enter the run-off area at the end of each lap, and insert your next card into a machine and the boom is lifted and off you go.

The “pit area” is always filled with interesting cars and there’s a café that sells food, coffee and alcohol! New Zealanders may not understand the whole Nordschleife experience — but the Germans are remarkably sophisticated when it comes to such things.

Cameras are not encouraged — the gate-keepers will say “Nein!” if they see one in your car as you go out onto the circuit, but most Nordschleife regulars have permanent video cameras mounted on their cars, usually behind the radiator grille.

There’s a lot of nudge-nudge, wink-wink about driving here.

There are a lot of crashes and people die here often — but it is seldom spoken of and even less often are such incidents reported.

You are not supposed to used rental cars here, but again, nudge-nudge, wink-wink. There’s a story that a man crashed his rental car. Track crews were on the job quickly — they are constantly on the move, recovering crashed cars or repairing damaged Armco. They saw this was a rental car, badly damaged and knew the insurance company would not pay. So, for the exchange of a bundle of Euros, they called in a tow truck from outside, the car was taken several km away from the place and pushed over a bank. So it became a road crash.

On one visit, I had the Navigator riding shotgun. We had been a week on the road and the interior of the car was awash with stuff we had accumulated.

I bought six laps and asked her to take photographs once we were on the circuit. But she didn’t want to, so I held the camera out the driver’s window and drove around the place at a modest enough pace, snapping away — which you can do with modern electronic cameras. But the luggage was sloshing and crashing about the interior of the car. We had a lot of faster traffic howling past us — bikes, AMG Mercs, Schnitzer BMWs, the odd Lambo, but we managed to pass a coach and a people mover.

But when we got back to the pit area she was out of the car in a flash — “I’m not doing that again, you are a lunatic! Go by yourself!” she said as she headed for the café.

I had my photographs, so for the next five laps I just concentrated on my driving.

The lasting memory of driving the Nordschleife is of constantly changing tarmac, edged by grassed run-off areas and Armco. The length is both a constant challenge and bewildering. Every corner has hundreds of black tyre marks from skids and crashes and fans have sprayed graffiti over many parts of the track. And you can see how many crashes there are by the amount of shiny new Armco there is.

It’s a long, long way around this place and it’s just one of the greatest experiences you can ever have. The ultimate responsibility is yours — you can drive as fast, or as slow, as you like and nobody will judge you.

You must be logged in to post a comment.